Posted on Sep. 9th 2009 by Amelia

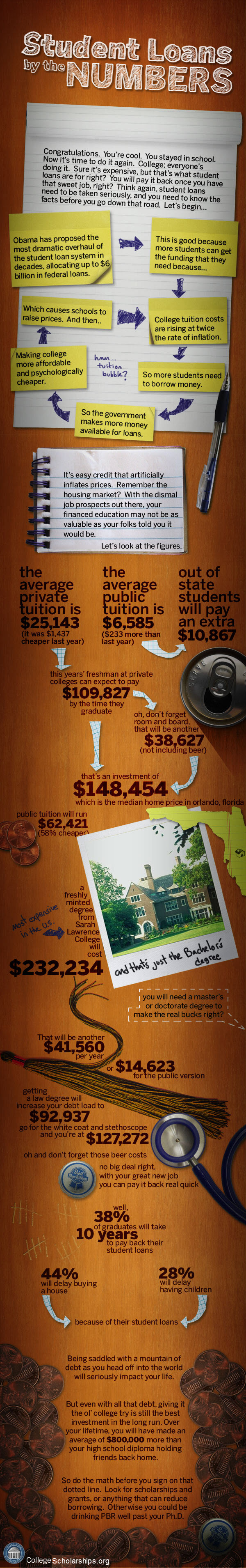

According to Anne Marie Chaker at the Wall Street Journal, “New numbers from the U.S. Education Department show that federal student-loan disbursements—the total amount borrowed by students and received by schools—in the 2008-09 academic year grew about 25% over the previous year, to $75.1 billion.”

The overall news may not be shocking to most people, after all the amount of money students borrow for school has been rising steadily in recent years. But the key number here is the size of the increase.

To put the 25% increase in perspective, we turn back to the WSJ.

To put the 25% increase in perspective, we turn back to the WSJ.

“…last year far surpassed past increases, which ranged from as low as 1.7% in the 1998-99 school year to almost 17% in 1994-95.”

In addition to the increase in borrowed funds, the percentage of students taking out loans to pay for school is also on the increase. Today, nearly 70 percent of college students are borrowing funds to help pay for school. Just 12 years ago, the percentage of borrowers totaled 58%.

To get a sense of this distressing trend and its impact on students, the Journal offers a number of frightening examples. First, they discuss the plight of “Kordi Solo, a senior majoring in journalism at Central Michigan University,” who “expects to owe about $60,000 in student loans by the time she graduates in the spring.” Later they tell the tale of “Zack Leshetz, a 30-year-old lawyer in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.,” who “has $175,000 in student loans from his seven years in college and law school.”

Even with a law degree, Leshetz lives paycheck to paycheck. And while Leshetz is struggling, Solo might be in an even worse position at one-third the debt level. Given the extent to which the journalism field has been hammered by the recession and an evolving media model, her accumulated debt could well be insurmountable.

Losing Investment?

The impact of this borrowing on students and their future opportunities is significant. Chaker notes:

“The ripple effects for today’s heavily indebted young people are becoming palpable. A growing body of research suggests that tough loan payments are affecting major life decisions by recent graduates, forcing them to put off traditional milestones—from buying a first home to even marriage and having children.”

While most everyone continues to tout the college degree as a must for future job options, Chaker notes that borrowing such sums to obtain that coveted sheepskin put students into a tough spot when they first enter the world of work.

These numbers and the impact on major life decisions have Karl Denninger of Market-Ticker uttering some almost unthinkable words:

“Students are literally coming out of college with more debt than they can ever reasonably hope to amortize over their working lives, making their education a negative net equity position – that is, a guaranteed losing investment.”

In other words, the debt load accrued by the majority of students is so large that even with the greater pay associated with a job based on earning a degree, that pay is not enough to cover both the costs associated with taking care of oneself and the debt payments that must be made.

Borrowing Begets Higher Costs and an Additional Need for Loans

As but another sign the system is not working, it seems that all the borrowing ultimately is triggering an even greater need to pursue loans.

“The rising levels of borrowing,” writes Chaker, “may ironically be contributing to the accelerating cost of college, say some college-finance experts. Loans can give colleges an artificial sense of a family’s ability to pay tuition.

“To some extent, that false sense of security gets built into the assumptions schools make when setting prices, say experts.

“To some extent, that false sense of security gets built into the assumptions schools make when setting prices, say experts.

“The idea is that as prices rise, families borrow more and more, spurring prices to rise further, which in turn requires more borrowing.”

The untenable position students are finding themselves in has Seth Godin insisting that higher education may well be at the crossroads.

Godin suggests that higher education is going to have to make basic decisions in three distinct areas moving forward.

- Should higher education be scarce or abundant?

-

Should higher education be free or expensive?

- Should higher education be about school or about learning?

Currently, Godin suggests that college tends to be focused on scarce, expensive schooling. The result could be categorized as a monopolistic format.

Students can only obtain a college degree by spending gobs of money to gain access to specific curricula at institutions that have ascertained accreditation. Yet once in an institution, there is little emphasis on what a student has actually learned. Instead, credits are paid for and collected and when enough money is spent and enough credits accumulated the degree is awarded.

Godin instead imagines what higher education might be like if a school were to be built around inexpensive, abundant learning. A place where an unlimited number of materials were made available for a modest fee and the emphasis was not on charging per course or per credit, but for access, with a degree awarded based not on the courses or credits or fees, but on demonstrated knowledge.

One Option Exists

While most students continue along the traditional path, one that is taking too many down a road of false promises of future prosperity, it is interesting to see that one company today is challenging the status quo.

A new educational entity called StraighterLine is delivering Godin’s suggested option, offering online courses in subjects like accounting, statistics, and math for a flat rate of $99 a month. Instead of a per course or per credit fee, the rate is $99 for the month. In addition, instead of a semester or yearly or four year degree schedule, there are no semesters or defined calendars.

You as a student decide how many courses you want to take at a time and for how long you want to take them. Instead of heading off to some distant location or stopping your schedule to meet that of higher education, you work online, from home.

Students can “access course materials, read text, watch videos, listen to podcasts, work through problem sets, and take exams” all over the internet. In addition, to make the program more consistent with one critical aspect for learning (the need for a sense of community) StraighterLine also features online study groups where students can collaborate with one another via a “listserv and instant messaging.”

Most importantly, tutors are available to help students when they need additional support. These support personnel are available any time, day or night, and there is no extra costs for accessing such services.

A student completing a traditional college semester of 15 weeks and 15 credit hours in the traditional time frame would spend a total of just $400. Compare the cost of one full year under such a format with the numbers bandied about today for America’s elite colleges, as much as $40 and $50 thousand per year if a student chooses to live on campus.

StraighterLine is actually the idea of a man named Burck Smith. The entrepreneur has created an educational model that seems to fit Godin’s inexpensive, abundant learning concept by getting some other established (i.e., accredited) colleges to allow the transfer of credit from Straighter Line to the traditional learning model.

This is ultimately the biggest hurdle as it allows learners to earn that coveted diploma from an accredited institution. In other words, at the end of the line they have that all-important degree.

StraighterLine is indeed a new model, one where students are not tied to some college campus or program. Instead, students can assemble a degree from various course providers from their own computer.

More importantly, they can do so at a cost that is reasonable, a step that protects their long term fiscal future. Perhaps most importantly, it is a step WashingtonMonthly.com sees as a proper one for higher education.

It may be some time before the “Internet bomb explodes in its basement,” writes Kevin Carey. “The fuse was only a couple of years long for the music and travel industries; for newspapers it was ten.

It may be some time before the “Internet bomb explodes in its basement,” writes Kevin Carey. “The fuse was only a couple of years long for the music and travel industries; for newspapers it was ten.

“Colleges may have another decade or two, particularly given their regulatory protections. Imagine if Honda, in order to compete in the American market, had been required by federal law to adopt the preestablished labor practices, management structure, dealer network, and vehicle portfolio of General Motors. Imagine further that Honda could only sell cars through GM dealers. Those are essentially the terms that accreditation forces on potential disruptive innovators in higher education today.”

Time for a Change

We would like to think the fuse has been lit, that the current accumulating debt loads being assumed by college students would be cause for society to demand a new model for higher education.

Yet, because it is so early in the process, StraighterLine is likely to seem a bit too much cutting edge, a little too groundbreaking and novel for a public that tends to prefer tradition. It is also, dare we say it, a little too inexpensive to be considered a viable alternative by a populace that equates higher cost with higher quality.

But with accruing debts making the current model a net negative for students at precisely the same time that society is placing greater emphasis on earning a college degree, more cost-effective methods must be created.

That would indicate that we are at the crossroads as Godin postures, a time when higher education does move from its current scarce, expensive schooling format to one that features a more abundant, cost-effective learning model.

While some economists believe the recession is over, this data reveals that the recession could well be a double-dipper, if not a stagnator. The high unemployment rates mean that a large segment of America still has little in the way of disposable income and will remain in such a plight for the near future.

While some economists believe the recession is over, this data reveals that the recession could well be a double-dipper, if not a stagnator. The high unemployment rates mean that a large segment of America still has little in the way of disposable income and will remain in such a plight for the near future.

The concept of simulation as a tool has been used for a long time in aviation. As part of their training, pilots use machinery that replicates the key elements of flying a plane. In addition to normal everyday flights, these simulators test advanced skills by presenting challenges to the pilot in the form of technical malfunctions or the effects of severe weather.

The concept of simulation as a tool has been used for a long time in aviation. As part of their training, pilots use machinery that replicates the key elements of flying a plane. In addition to normal everyday flights, these simulators test advanced skills by presenting challenges to the pilot in the form of technical malfunctions or the effects of severe weather. Making only the minimum payments ensures you will be in debt for the longest possible time. Paying the typical minimum level for a $500 debt at current interest rates of 15-20 percent will keep you in debt for more than a decade, even if you never charge another item.

Making only the minimum payments ensures you will be in debt for the longest possible time. Paying the typical minimum level for a $500 debt at current interest rates of 15-20 percent will keep you in debt for more than a decade, even if you never charge another item. However, you have probably heard on television or seen online an ad by some third party company that can help you eliminate your debt. While there are legitimate agencies that do provide such services, many other entities are simply hoping to take advantage of your plight. If you are not careful, you may soon find one of these companies is bleeding you worse than your credit card company.

However, you have probably heard on television or seen online an ad by some third party company that can help you eliminate your debt. While there are legitimate agencies that do provide such services, many other entities are simply hoping to take advantage of your plight. If you are not careful, you may soon find one of these companies is bleeding you worse than your credit card company.  To put the 25% increase in perspective, we turn back to the WSJ.

To put the 25% increase in perspective, we turn back to the WSJ.  “To some extent, that false sense of security gets built into the assumptions schools make when setting prices, say experts.

“To some extent, that false sense of security gets built into the assumptions schools make when setting prices, say experts.  It may be some time before the “Internet bomb explodes in its basement,” writes

It may be some time before the “Internet bomb explodes in its basement,” writes  But most were merciless in their criticism of the 27-year-old. Robbie Cooper at

But most were merciless in their criticism of the 27-year-old. Robbie Cooper at  The availability to readily access information on the web about a candidate has created a whole new phenomena called personal branding. It is a concept every high school and college student needs to become aware of and breaks down simply: it is extremely important that when your name is Googled, positive information comes up.

The availability to readily access information on the web about a candidate has created a whole new phenomena called personal branding. It is a concept every high school and college student needs to become aware of and breaks down simply: it is extremely important that when your name is Googled, positive information comes up.  For years, the generally accepted figure associated with earning a college diploma has been $1 million. Those calculated additional earnings a college graduate earns in his lifetime above and beyond of a classmate with just a high school diploma continue to be used as the rationale for earning that coveted diploma.

For years, the generally accepted figure associated with earning a college diploma has been $1 million. Those calculated additional earnings a college graduate earns in his lifetime above and beyond of a classmate with just a high school diploma continue to be used as the rationale for earning that coveted diploma. As a monetary investment that number still seems reasonable. We certainly can advocate spending $60,000 knowing full well we can one day expect to pocket $280,000 as a result. Add in the ability to better control one’s career choice and the investment seems to be a no-brainer.

As a monetary investment that number still seems reasonable. We certainly can advocate spending $60,000 knowing full well we can one day expect to pocket $280,000 as a result. Add in the ability to better control one’s career choice and the investment seems to be a no-brainer. At the university level, you will also meet many interesting people and have access to adults who are willing to help you learn new things. Once in the world of work, there will be far fewer people willing to help you become successful.

At the university level, you will also meet many interesting people and have access to adults who are willing to help you learn new things. Once in the world of work, there will be far fewer people willing to help you become successful. That’s right, a button that would authorize the IRS to collect, summarize and drop the pertinent data already submitted during prior tax seasons into the form in the appropriate places. And with that step, the form we all have to do to be eligible for federal financial aid, the form that everyone, sooner or later comes to despise might actually be on the way towards being reasonable and dare we say it, user-friendly.

That’s right, a button that would authorize the IRS to collect, summarize and drop the pertinent data already submitted during prior tax seasons into the form in the appropriate places. And with that step, the form we all have to do to be eligible for federal financial aid, the form that everyone, sooner or later comes to despise might actually be on the way towards being reasonable and dare we say it, user-friendly. According to the U.S. Department of Education, the FAFSA included 153 questions, some of which were not asked for when parents or the student filed their income taxes. The sum total for the DOE is that the form has ultimately been more difficult than filing income taxes.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, the FAFSA included 153 questions, some of which were not asked for when parents or the student filed their income taxes. The sum total for the DOE is that the form has ultimately been more difficult than filing income taxes.  Under the IBR plan, the loans eligible for consideration include: all Federal Direct Loans (FDL) and federally guaranteed loans (FFEL) including subsidized and unsubsidized Federal Stafford loans; Federal Grad PLUS loans (but not Parent PLUS loans); and Federal Direct Consolidation loans. Federal Perkins Loans are only eligible when part of a Federal Direct Consolidation Loan.

Under the IBR plan, the loans eligible for consideration include: all Federal Direct Loans (FDL) and federally guaranteed loans (FFEL) including subsidized and unsubsidized Federal Stafford loans; Federal Grad PLUS loans (but not Parent PLUS loans); and Federal Direct Consolidation loans. Federal Perkins Loans are only eligible when part of a Federal Direct Consolidation Loan. The time period for public service is retroactive to October 1, 2007 meaning those borrowers who have already elected public service may begin counting the ten year period at that point. Some restrictions occur for those who had already consolidated their loans and those restrictions may move the eligible period forward to July 1, 2008.

The time period for public service is retroactive to October 1, 2007 meaning those borrowers who have already elected public service may begin counting the ten year period at that point. Some restrictions occur for those who had already consolidated their loans and those restrictions may move the eligible period forward to July 1, 2008.  For reporting purposes, the school was supposed to be sending along the number of full-time faculty members that met the prestigious status. Turns out, of the 34 listed on the web site, 17 did not meet the criteria set forth by U.S. News.

For reporting purposes, the school was supposed to be sending along the number of full-time faculty members that met the prestigious status. Turns out, of the 34 listed on the web site, 17 did not meet the criteria set forth by U.S. News.